The Forgotten Orientalism: When Arab Scholars Described Europe (9th–15th Century)

These authors did not produce a symmetrical “Occidentalism” comparable to modern Orientalism. Rather, they left behind a corpus of texts reflecting a structured, attentive, and often admiring external gaze directed at Christian Europe. Scattered across Arabic geographies, encyclopedias, chronicles, and travel narratives, this material reveals far more than simple description: it testifies to the circulation of knowledge, the mobility of scholars, the existence of intellectual diplomacy, and the depth of Mediterranean exchanges.

The First Gaze: Encyclopedic Geographers (9th–11th Century)

One of the earliest scholars to offer a systematic description of Europe was al-Yaʿqūbī (d. 897). In his Kitāb al-Buldān (Book of Countries), he clearly distinguishes between Franks, Lombards, Slavs, Byzantines, and the peoples of the northern seas. He notes differences in governance, religious practices, and social organization, emphasizing Europe’s internal diversity—an insight that contemporary Latin chroniclers often conveyed only indirectly.

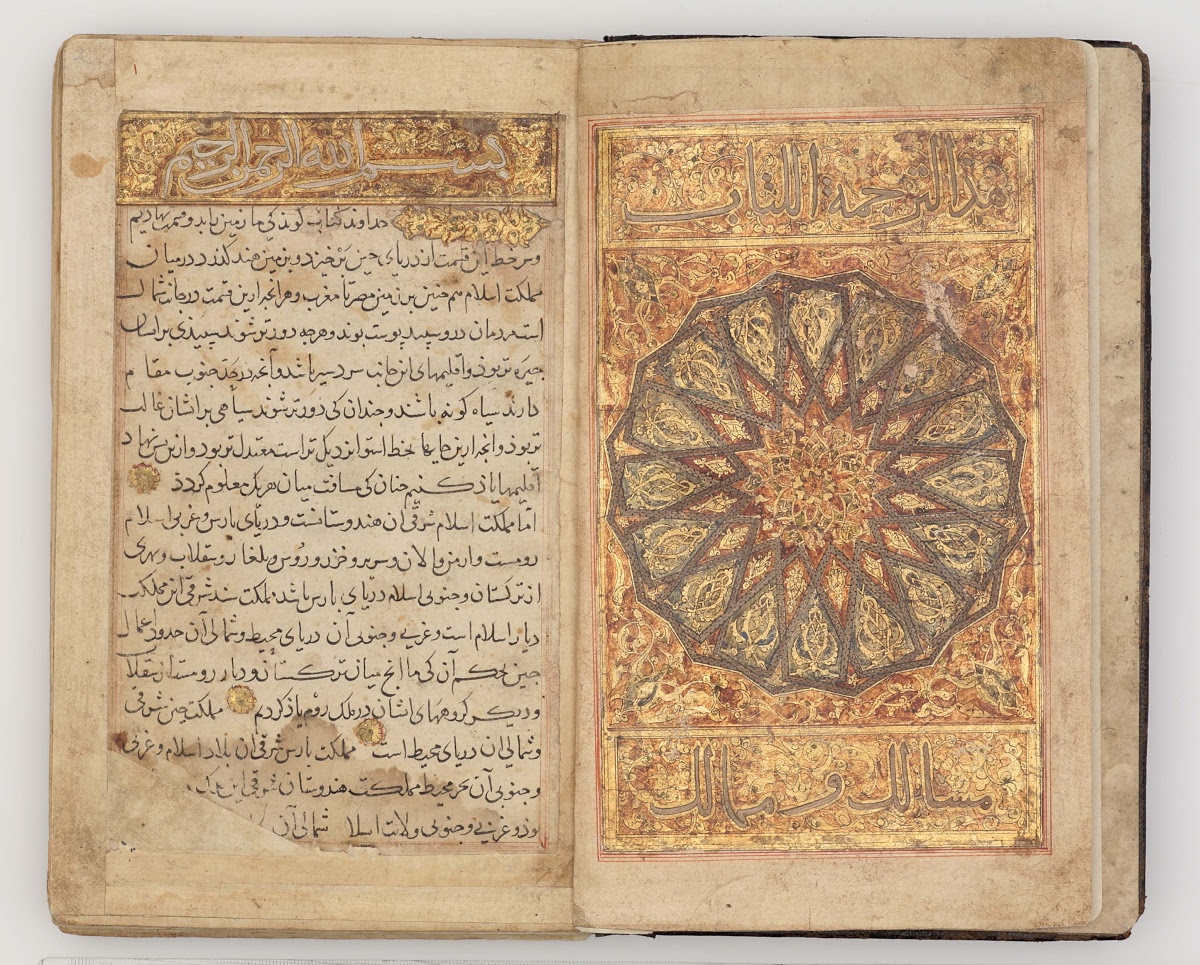

His contemporary Ibn Khurradādhbeh (9th century), in Kitāb al-Masālik wa-l-Mamālik (Book of Routes and Realms), describes the commercial networks linking Baghdad to European cities such as Lyon, Rome, Bari, Barcelona, and even the Rhineland. His work demonstrates a detailed understanding of economic systems, customs duties, currencies, and the commercial practices of Western Christians.

The masterpiece of this period, however, remains the work of al-Masʿūdī (d. 956), often referred to as “the Herodotus of the Arabs.” In Murūj al-Dhahab (The Meadows of Gold), he offers an extraordinarily rich portrait of the Mediterranean world, describing northern peoples with striking candor and recording ethnographic details—dietary habits, hairstyles, music, funerary practices—that lend his work a rare anthropological depth for the 10th century.

Of the Franks, he writes:

“They are steadfast in their commitments and loyal in their alliances, despite their roughness.”

A nuanced judgment, sharply contrasting with the reciprocal stereotypes often highlighted in later narratives.

The Decisive Contribution of the Muslim West: al-Andalus as Europe’s Observatory

In al-Andalus, Europe was not a distant horizon but an immediate neighbor. Andalusi scholars observed Europe through daily contact, lending their descriptions unparalleled depth.

In the 11th century, Abū ʿUbayd al-Bakrī (d. 1094), in his Kitāb al-Masālik wa-l-Mamālik, produced the first comprehensive Arabic description of Normandy, Brittany, Aquitaine, the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, and Christianized Scandinavia. He relied explicitly on non-Muslim informants—merchants, diplomats, travelers—whom he named. His work represents the first Mediterranean geography to devote detailed attention to northwestern Europe.

The Cordoban historian Ibn Ḥayyān al-Qurṭubī (d. 1075) described Frankish embassies, the structure of Christian armies, and the political role of bishops in warfare. He analyzed neighboring Iberian Christian kingdoms with striking political realism, recognizing them as genuinely “structured political powers,” rather than dismissing them as peripheral or barbarian.

In the 12th century, the work of al-Idrīsī (d. 1165), geographer at the Norman court of Sicily, stands as the most sophisticated medieval attempt to map Europe. His Nuzhat al-Mushtāq (The Book of Pleasant Journeys) offers meticulous descriptions of European cities, rivers, climates, and routes—from Scotland to Bohemia, from Provence to Scandinavia. Written in Arabic for a Christian king, the text embodies a genuinely Mediterranean intellectual world.

Diplomacy, Trade, and Curiosity: Arab Travelers in Europe

Muslim travelers to Europe were fewer than geographers, but their accounts are all the more valuable.

The most famous is Ibrāhīm ibn Yaʿqūb (10th century), a Jewish Andalusi diplomat serving the Umayyad caliph. His journey to the court of the Ottonian emperor—preserved through al-Bakrī—remains one of the most detailed testimonies of medieval Central Europe. He describes Prague, Cologne, Saxony, monetary systems, market organization, Christian festivals, and urban layouts. His tone is neither condescending nor hostile; it is analytical and attentive.

In the 11th century, Abū Bakr al-Turṭūshī, an Andalusi jurist, traveled through Italy—Pisa, Amalfi, Bari—and reported on urban life, republican institutions in maritime cities, and commercial practices. He compared Italian justice with Islamic courts without ranking them hierarchically—an exceptional stance in medieval legal literature.

By the 13th century, diplomatic exchanges between the Arab world and Italian city-states, particularly Genoa, generated a series of notes and partial accounts that, though fragmentary, confirm the continuity of this observational tradition.

A Structured Gaze: Pragmatism, Curiosity, and the Absence of Religious Obsession

What stands out across these texts is the non-theological tone of the Arab gaze upon Europe. Medieval Islam did not construct a Christian “otherness” comparable to the Muslim otherness forged in Latin Europe. Religious differences are noted, but rarely absolutized.

Descriptions focus primarily on:

- political organization (kingdoms, succession, warfare),

- social practices (food, family roles, rituals),

- commerce (routes, weights, currencies),

- climate and human geography,

- language (families, phonetic affinities).

As scholars such as Miquel Barceló and André Miquel have observed, this approach reflects a fundamentally earthly conception of knowledge: understanding others in order to navigate an interconnected world.

Why Was This Orientalism Forgotten?

Several factors contributed to the disappearance of this perspective from later narratives:

- The rise of European Orientalism in the 18th–19th centuries, framed as a “scientific” study of the East.

- The absence of a symmetrical conceptual category in Arabic; these texts were never theorized as a medieval “Occidentalism.”

- The decline, after 1492, of Andalusi and Sicilian centers of intellectual production.

- The loss of countless manuscripts during political upheavals in Sicily, al-Andalus, and Ifriqiya.

Yet these texts remain of exceptional value. They reveal a medieval Arab world that was curious, connected, and free of provincialism—capable of describing Europe not as a barbarian periphery, but as a constellation of complex societies worthy of attention, comparison, and understanding.