How the Arab world shaped the library as a public space

Baghdad: the cradle of the public library

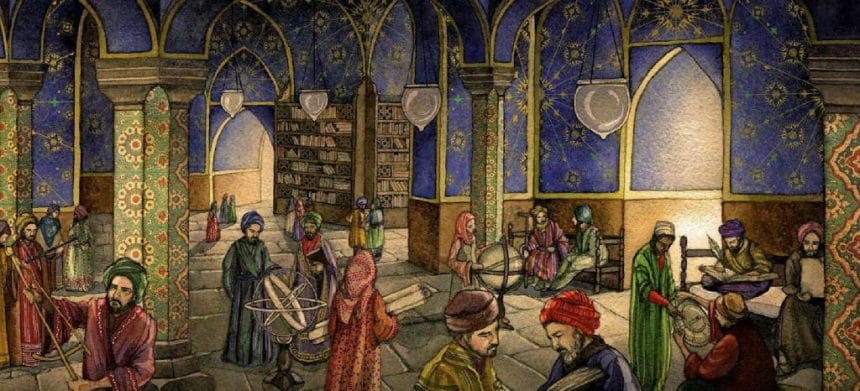

The most emblematic example remains Baghdad, the Abbasid capital founded in 762. From the reign of al-Maʾmūn (813–833), the city housed the celebrated Bayt al-Ḥikma, or House of Wisdom. Long romanticized as a simple translation bureau, it appears in Arabic sources, notably al-Nadīm’s Fihrist (d. 995) and Ibn al-Qifṭī’s Kitāb Ikhbār al-ʿUlamāʾ bi Akhbār al-Ḥukamāʾ (d. 1248), as a scholarly complex where Syriac translators, Persian physicians, Indian mathematicians, and Muslim philosophers worked side by side.

The Bayt al-Ḥikma included reading rooms, a scriptorium, manuscript repositories, and at times even astronomical observatories. Most importantly, it was open. External readers, including students and local scholars, could consult manuscripts and attend public readings known as majālis. As Dimitri Gutas has shown in Greek Thought, Arabic Culture, many translations and copies produced there circulated far beyond the institution itself, and a substantial portion of Baghdad’s educated population had access to them.

This openness should not be idealized, but it represents a conceptual rupture. The library became an urban space rather than a restricted archive. Political tensions, theological debates, and doctrinal reconfigurations of the period passed through this space.

The Fatimid model: Cairo and the "House of Knowledge"

In the eleventh century, a second model emerged with the founding of the Dār al-ʿIlm, or House of Knowledge, in Cairo in 1005 under the Fatimid ruler al-Ḥākim. In his Khiṭaṭ, al-Maqrīzī (d. 1442) describes an institution endowed with tens of thousands of manuscripts that were freely accessible to all readers. Visitors were provided with paper, ink, pens, and lecterns, which constituted a remarkable innovation. Teachers of theology, law, grammar, and philosophy delivered public lectures. The Dār al-ʿIlm did not serve the state. It served knowledge.

Sunni and Shiʿi Muslims, Jews, and Christians encountered one another there. The space was not doctrinally exclusive but functioned as a platform for learning and as an intentionally non-confessional educational environment. By guaranteeing universal access to books, the Fatimids pursued a political project that made knowledge a source of legitimacy. The broader effect, however, was social. The library became a shared civic space.

Al-Andalus: Córdoba, the city of books

At the same time, in the western Islamic world, the Umayyad library of Córdoba, enriched under Caliph al-Ḥakam II (961–976), assembled several hundred thousand manuscripts. Its catalogue reportedly exceeded forty volumes. Andalusi chroniclers such as Ibn Ḥazm, Ibn Bashkuwāl, and Qāḍī Ṣaʿīd al-Andalusī describe a city in which bookshops, copying workshops, and both private and public libraries formed a true republic of the book.

Unlike contemporary monastic scriptoria in Europe, which were closed and specialized, Córdoba was characterized by horizontal dissemination. Manuscripts were sold in markets, books circulated among scholars, and libraries were open to students of modest means. Access to books was not merely a privilege. It was an element of urban life.

The Maghreb and West Africa: Teaching libraries and family collections

In the Maghreb, the library attached to the Qarawiyyīn in Fez from the ninth to the twelfth centuries functioned as a place of study and consultation. Muḥyī al-Dīn Ibn ʿArabī (d. 1240), in his autobiographical writings, evokes long hours spent reading in public and private libraries in Seville, Fez, and Marrakesh.

Further south, the private libraries of Timbuktu in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, described by John Hunwick and Mauro Nobili, extended this tradition in a Sahelian context. These were family collections open to students, with practices of manuscript lending, rental, and dissemination through local copying. The book became both a vehicle of intergenerational transmission and a marker of scholarly prestige, as well as an economic asset.

Libraries as scholarly democracies

One fundamental feature distinguishes these libraries from their ancient predecessors. They did not exist solely to preserve texts or to legitimize political power. They functioned as urban institutions, often funded by charitable endowments known as waqf, and were designed to make reading accessible.

In the Muqaddima, Ibn Khaldūn emphasizes the role of mutual interaction in the advancement of the sciences. The library, in this view, is a place of conversation. Texts are read aloud, commented upon, corrected, and debated. Manuscripts are not sacred as objects. They are alive as tools.

This culture of the book was further enabled by the widespread adoption of paper, introduced into the Islamic world in the eighth century following the Battle of Talas. As Jonathan Bloom shows in Paper Before Print, paper was cheaper and more flexible than parchment, making large urban libraries and wide circulation of books possible.

Classifying the world: the birth of bibliography

These libraries also produced another decisive innovation, namely classification. Al-Nadīm’s Fihrist (988), a true universal catalogue, lists books available in Baghdad and across the known world, organized by disciplines, schools, and religions. It stands as one of the earliest bibliographic repertories in history and reflects a keen awareness of the book as a structured universe open to inquiry.

Libraries in Damascus, Aleppo, Mosul, and Nishapur also produced inventories, often embedded in scholarly biographies. The very idea that one might access books through a list was itself an innovation.

A global invention, not an exception

To say that the Arab Islamic world invented the public library does not mean that nothing comparable existed elsewhere. It means that it was in Islamic lands that the library first became an open place, a space of teaching, a public service, an instrument of circulation, and a civic institution in which books shaped collective life.

In this world, the library was neither a temple nor a treasure vault. It was a hanging garden of books, a living space where texts grew, circulated, and responded to one another. It anticipated, by several centuries, the modern library.