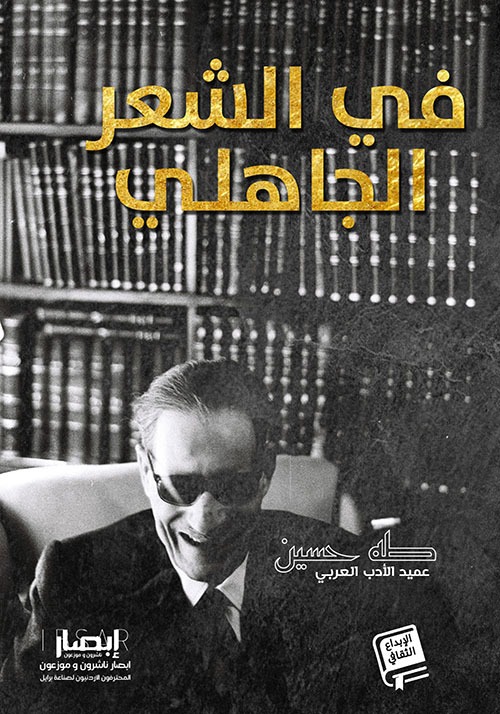

« On Pre-Islamic Poetry » by Ṭāhā Ḥusayn: A Shock That Awakened Arab Literary Criticism

A Thunderclap in a Too-Quiet Sky

At the time, attachment to classical texts — especially those of the Jāhiliyya (pre-Islamic period) — was often tinged with cultural devotion. Pre-Islamic poetry was seen as a mirror of authentic Arab identity, a source of linguistic pride, a monument of ancestral honor. To question its authenticity was to shake the very symbols of Arabness.

Yet Ṭāhā Ḥusayn did not hesitate. From the opening lines of his book, he sets the tone:

“Here is a new way of studying the history of Arabic poetry — one our readers are not used to. I am almost certain that some will reject it angrily, while others will simply turn away.”

He claims the right to ask direct questions, rejecting rhetorical caution and pious detours. His ambition: to open a rational debate within a culture still steeped in literary sanctity.

The Central Hypothesis: A Reconstructed Tradition

At the heart of Ṭāhā Ḥusayn’s argument lies a bold yet methodical idea: the corpus of so-called pre-Islamic poetry is historically unreliable. In his view, it is not a faithful reflection of pre-Islamic Arab society but rather a body of texts assembled later — partly motivated by ideological aims.

To support his thesis, he uses the Qur’an as a point of comparison. To him, the sacred text, revealed at a pivotal moment in Arab history, better reflects the language, religious consciousness, and worldview of 7th-century Arabs. And yet, he observes a stark linguistic and thematic gap between the Qur’an and what is called “pre-Islamic poetry.”

“The Qur’an represents the religious life of the Arabs more faithfully than what we call Jāhilī poetry.”

He further notes that the language of these poems does not match the dialectal diversity attested in pre-Islamic Arabia. He suggests that a unified literary language was developed only after the rise of Islam — raising doubts about the true origins of the texts.

“We maintain that this poetry does not represent the authentic language of the ancient Arabs. We must first discover what that language truly was.”

Questioning Intention and Power

More provocatively, Ṭāhā Ḥusayn asks what ideological motives might have shaped this poetic heritage. He alludes to movements such as the Shuʿūbiyya — post-Islamic intellectual circles that sought to valorize non-Arab cultures, particularly Persian, in response to Arab dominance.

“And the Shuʿūbiyya — what should we think of their possible role in inventing poems and stories attributed to the ancient Arabs?”

With this question, he introduces a critical suspicion: what if part of this poetic tradition was fabricated or reshaped to serve tribal, religious, or political interests in the Abbasid period? What if, instead of reflecting ancient Arabia, it had been used to construct an idealized — and instrumentalized — vision of the past?

Reactions: From Outrage to Intellectual Awakening

Reactions were swift and fierce. Accused of insulting the Arabic language, Islamic history, and even the Qur’an, Ṭāhā Ḥusayn was forced to withdraw the book and publish a censored version soon after. But the debate was already ignited. Conservative scholars accused him of applying Western critical methods unsuited to the Arab tradition. Others reproached him for ignoring oral transmission, thus distorting his conclusions.

Yet a new generation of thinkers saw in his work a necessary shock. Critics such as Ibrāhīm al-Māzinī, Muḥammad Mandūr, and later Naṣr Ḥāmid Abū Zayd viewed the book as a milestone in the emergence of a historical and desacralized approach to Arabic literary heritage. On Pre-Islamic Poetry became foundational — not for the answers it offered, but for the questions it dared to ask.

A Living Methodological Legacy

One of the book’s great strengths lies in its methodological rigor. Ṭāhā Ḥusayn does not rely on intuition alone; he grounds his analyses in linguistic comparison, critical evaluation of sources, and sensitivity to the political dimensions of literary transmission. He calls for a scientific approach to Arabic texts, inspired by modern philology.

This intellectual stance opened the door to interdisciplinary readings — integrating history, sociology, and linguistics. It liberated Arab literary criticism from a sacred attachment to the text and encouraged viewing heritage as a historical construct rather than an untouchable absolute.

An Invitation to Think — Still Today

A century later, On Pre-Islamic Poetry remains essential reading. Not because it provides final truths, but because it redefined what could be thought. It showed that one can love a text without idealizing it, and honor a tradition without freezing it in time.

More broadly, Ṭāhā Ḥusayn reminded readers that Arab modernity cannot be built without a critical relationship to its own cultural foundations. His aim was never to reject heritage — but to free it from blind sanctity. To introduce reason, not to destroy, but to understand.

Through his clarity, rigor, and intellectual courage, Ṭāhā Ḥusayn offered the Arab world a lesson still urgent today: to think is to question what we think we know. On Pre-Islamic Poetry is not a book of rupture, but of renewal — an invitation to treat heritage not as a shrine, but as a living space for dialogue between past and present.

To read Ṭāhā Ḥusayn today is to relearn how to doubt without denying, to critique without destroying, and to inherit without submitting — a task more necessary than ever.